A Reading Life

We owe it to every school kid to give them that life.

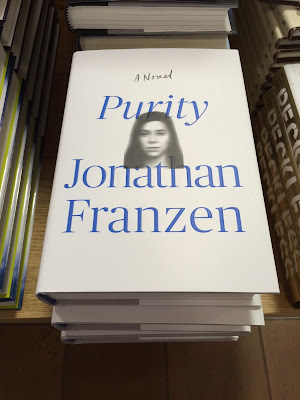

Here’s how Jonathan Franzen’s new novel Purity starts

off:

MONDAY

‘Oh pussycat, I’m so glad to hear your voice,’ the

girl’s mother said on the telephone. ‘My body is betraying me again. Sometimes

I think my life is nothing but one long process of bodily betrayal.’

‘Isn’t that everybody’s life?’ the girl, Pip, said. She’d taken

to calling her mother midway through her lunch break at Renewable Solutions. It

brought her some relief from the feeling that she wasn’t suited for her job,

that she had a job that nobody could be suited for, or that she was a person

unsuited for any kind of job; and then, after twenty minutes, she could

honestly say that she needed to get back to work.

In two quick paragraphs you are with people who you hear as

real. You even see them as real.

You want to be with them more. You want to read more conversations like

that. You want the kind of candor that Pip has given you already about her job.

Immediately you are not alone. You are not the only one with

problems in your life.

That’s why readers read.

It is a great sin to not see to it that the school children

of this city acquire competent reading skills. There is no other reason as

important as that to go to school. How

will they know they are not alone, if they can’t read well enough to read

books? When will they sit in the quiet and be involved like you can be with a

book? What kind of life will they have?

When you learned to read, it changed your life. The nuns told us when we made our First Communion

it would change our life. If it did, I didn’t notice. It was reading that

changed our lives. We could read comic books and baseball cards and sports

pages or library books we liked. A new world opened up. It was great to read stuff and talk to your

friends about it, or just think about it by yourself. It was even better than

listening to the Everly Brothers or watching Superman.

Don’t the mayor and the school heads read? Don’t they realize they wouldn’t have a good

job of any kind if they hadn’t learned to read well? Why do they not put their

foot down and say this is crazy--or sinful, as I would say--that so many kids aren’t

really readers when we’ve finished with them. Doesn’t it seem crazy to

them--again sinful --that kids come to them when they’re shiny and six years

old, and in the 10 years minimum that they are in the city schools, they

haven’t learned to read well enough in many cases to even pass the test to get

in the Army? Why haven’t the teachers raised their hands and said this is crazy

that what we’re doing is not producing the results it should; isn’t there a

better way?

Surprisingly for someone not inclined to business imagery,

spreadsheets often come to mind when I think about the schools and poor kids and

their reading problems. I remember 30 years ago looking at my accountant’s

computer that had a spreadsheet program.

I was trying to get money to start a weekly newspaper. We were inputting

various projected ad sales numbers to see what would add up to a profit or at

least a break-even number that might get an investor to throw in with us. It

was fascinating to me to watch how each new number we tried would shift all the

other numbers on the screen. One change changed everything.

Here’s why I think about that. What if this was added to the education mix?

What if we put into it the sentence that is on the sign I hold in front of the

Dept. of Education every weekday? WHY NOT TEACH EVERY SCHOOL KID TO READ WELL.

What if you put that into some imagined spreadsheet and all the other variables

shifted in a way that would say to everyone: More time has to be spent on

reading. If your team is missing free throws that are costing you games, then

you’d make them practice shooting free throws more every day at practice. Why

wouldn’t you then spend more time on reading, in all sorts of ways, including

private time every day for each kid to read what he or she wanted to read, like

I read baseball cards and sports pages? Why wouldn’t you have all the newest

books that Barnes and Noble has in your school library? And all the magazine

that kids might like? You put an article about Odell Beckham Jr. in front of

them and they’ll try to read it. Eventually they’ll learn to read it.

By law the schools have them for ten years, till they’re 16.

Why not make sure that in those 10 years, the kids, no matter where or who they

come from, are taught to read well. What else is competing for the school’s

time? And don’t say ‘tests’. Please. What else is competing? History? Math?

Science? A young teacher stopped by my sign one morning and said, ‘Exactly!’

She said she taught high school biology and the kids couldn’t read the

textbooks. What kind of game strategy is that? Shouldn’t they have been

practicing their free throws some more?

If you want to put poverty into the spreadsheet, go ahead.

If you want to put single mothers in, go

ahead. If you want to put gunshots in,

that too can go in. The bottom line on the spreadsheet may give you a number

you don’t want to look at. But it has to be looked at. And then action has to

be taken.

If the schools decided to tackle the problem once and for

all, the direction would be set. They’d know what to demand of the city and the

state to get the job done. They’d know who to hire to make it happen. The great

German philosopher Goethe says that if you really commit to doing something,

things will come out of the woodwork, that you didn’t foresee, to assist you.

When I started this newsletter almost five years ago, I

looked for a quote to put at the top of the page above everything else. I

Googled, I looked through books I had on my shelves, I went to the library.

Then I found this. I’d pick it again.

'We

go to college to be given one more chance to learn to read in case we haven't

learned in high school. Once we have learned to read, the rest can be trusted

to add itself unto us.'

-Robert Frost

-Robert Frost