Toni Morrison says it’s required reading. She‘s saying it about Ta-Nehisi Coates’s little 150-page book, Between the World and Me. It’s been out for some months now. It’s a letter to Coates’s 14-year-old son. You’ve heard about it. You may have read it. I’d say you should. But who I’m most interested in are the 14-year-olds in the city, school kids his son’s age. Could they read this book? Not as some over-analyzed, drawn-out homework project, a few baby pages a day. Could they just sit down with it or lie down with it, and read it, maybe in one or two sittings in their bedroom, like the letter it is? Coates wrote it for a 14-year-old. What if the schools here asked themselves if their 8th graders could easily read that book? Wouldn’t that be a good measure? There has to be some kind of measure. I’d say go with this one. And if they found that most of the kids couldn’t easily read it, which is what they’d find, then shouldn’t the schools change the way they spend their students’ time?

Some of the high school kids and college kids who walk past

my sign every day smile at it and me and say hi. A few Muslim girls go by with veils over

their faces. They smile big with their eyes and wave quietly.

I remember being 14. I was obsessed with the guy my

18-year-old sister was dating. His name

was William Kelly Young and he was from Boston. His parents were dead and he

lived with an old sea captain. He drove a little silver-gray sports car and

wore a camel-hair coat and his hair looked like a Kennedy’s. It was 1961 and

that was a big thing. It was winter when he first came to visit. I was out

shooting hoops in the half-shoveled driveway with a friend and he got out of

his little car with his long camel-hair coat on and his good hair and clapped

for the ball. I tossed it to him. I can

still see it. He swished the shot, even with his big coat on, with a real

shooter’s style, from 20-some feet. That

summer when he came to stay a few days with us, he was sitting on the porch one

night. I was looking at him. He was reading a paperback book. It was The

Catcher in the Rye, which I’d only vaguely heard of. Oh, did that look

cool to me. A guy who could shoot hoops

was reading a book in a crew-neck sweater on our porch. He was the coolest guy

to me sitting there slouched in a chair reading that book that he’d brought

from Boston to our little town with him. Their big love affair broke up, of

course, like those good things sadly do. I think of him though. I remain a

Celtics fan. And I’m a J.D. Salinger fan.

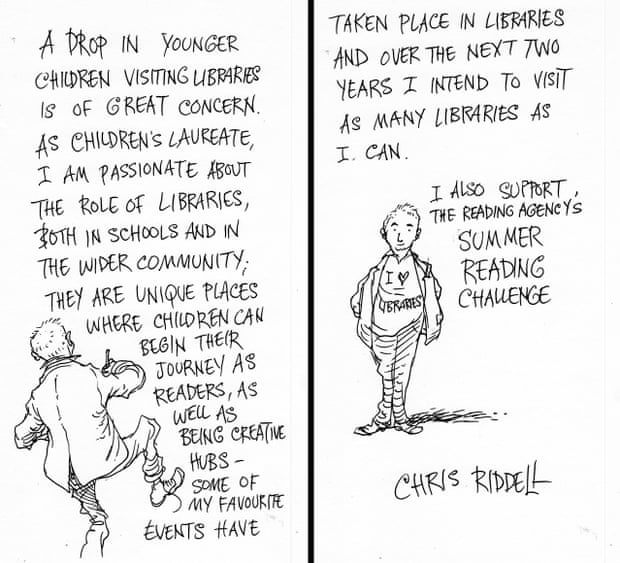

In my good city all the libraries would be open till 10:00

every night. I wonder why they aren’t open that late here. It’d be a great thing. Just think of it, a

clean well-lighted place, open every night to read books and magazines in. Kids

could do homework. To people who live places where their libraries are open

late, it surely surprises them that big-deal New York City’s libraries close

around dinner time.

There was an article in the Times last week

about two Upper West Side public schools whose boundaries may be re-arranged.

That’s a concern to the parents of kids in the white, more successful school

who don’t want things to change. They don’t want their kids to have to go to

the school where mostly black and Hispanic kids go. Nothing about that

surprised me. You know by now that’s how the world is. What did surprise me

though, in this day and age, was that the school where the poor kids go doesn’t

have a library.

I heard on an NPR talk show that there are more scripted TV

shows on now than ever in history. Like

400 of them. People don’t know how to see all the good ones. They binge-watch

to keep up. That seems crazy to me once

you’re out of the dorm.

The rates of illiteracy in prison are as high as you’d think

they’d be if you thought about it. How can that not be a pipeline? By law the

kids of the city have to go to school until they’re 16. That’s 10 years. To have

not learned to read in those 10 years is a big reason they’re in jail. Aren’t

schools supposed to teach kids to read? If you boil it down, are schools there

for any other reason?

You’ve heard how some young tennis players and young golfers

go off to special schools in Florida and out West to get intense training. Some kids from Europe and Asia come all that

distance to go to these schools. What

they get is instruction from people who know how to teach, and they get plenty

of time to work on their game. They get lots of reps. Lots and lots of reps.

Reps are important. In everything. Peyton Manning after the Broncos good game

against the Packers talked about the time they’d had in their off-week to go

over things. Like at the sports academies where the kids get the instruction

and all those reps, Peyton‘s coaches had the team go through their paces until

they had it figured out what they needed to do to get better, to get ready for

their big game. The schools here should

be like that. They should have good reading instructors, and plenty of time for

their students to get all the reading reps they need to become good readers who

when they’re fourteen can read books like Between the World and

Me. It would change their world. It

would make it better. It would make it safer.

Anyway, I keep

picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and

all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody's around - nobody big, I mean -

except me. And I'm standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do,

I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff - I mean if

they're running and they don't look where they're going I have to come out from

somewhere and catch them. That's all I do all day. I'd just be the catcher in

the rye and all. I know it's crazy, but that's the only thing I'd really like

to be.