from The Guardian:

Unputdownable! The bookshops Amazon couldn't kill

Sales of printed books have risen and shops are fighting back. As the online threat mounts, UK booksellers – from chains to pop-ups – tell us how they keep afloat

Books and bookshops are on the up. Sales of printed books have risen for the fourth successive year; sales of ebooks are falling; and, perhaps most encouraging of all, despite two recent high-profile store closures, the number of independent bookshops is growing again after decades of decline. Books – and readers who want to experience bookshops, rather than buy from Amazon – are not dead. The physical world lives on.

But what about booksellers? I’ve spent the past few weeks talking to a number of them: some responded to a callout on the Guardian’s website; others I approached directly. Most of the independents who responded are positive, although some are having to diversify to stay afloat. One has opened a tea room, while another I spoke to has closed her shop but plans to start selling children’s books from a boat. A would-be bookseller in Olney, Buckinghamshire, has bought a bus and hopes to sell children’s books from that. Shops are expensive to run, so bibliophiles are using their ingenuity.

The chain booksellers I spoke to were far less positive about their working lives. Waterstones has been doing well in recent years under the stewardship of James Daunt, bucking the predictions of those who said Amazon would kill it off. But recent arguments over pay and conditions have cast a long shadow, with a petition from staff to management calling for the introduction of a living wage and an open letter from 1,300 authors backing them. Daunt, in response to the petition, said of his booksellers: “We reward them as well as we can with pay, but we mainly reward them with a stimulating job.”

Still against all odds – book prices that have barely gone up in 20 years; the war waged by Amazon; price-cutting by the supermarkets; the lure of mobile devices – books and bookshops are fighting back. As the high street crumbles and life becomes ever more depersonalised, we should surely celebrate their resilience.

Rachael Rogan, 41, owner of Rogan’s Books in Bedford

Before she opened her bookshop in 2015, Rachael Rogan had never worked in books. She was a marketing executive specialising in preparing corporate bids for contracts. The turning point in her life came in her mid-30s when she was diagnosed with stage four cancer. “I managed to beat it,” she says, “but it does leave you with an ‘I’m going to do something I really care about’ attitude to life.”

She had two small children and decided the thing she really cared about was children’s books. She launched a children’s book festival and then, with the encouragement of members of the local community who pointed her to an empty shop space and pre-bought book vouchers to cash in once her shop was open, she took the plunge. “It’s been wonderful to see everybody come together and support it,” she says.

The rent is £15,000 and that doesn’t leave much for anything else. Rogan barely takes any salary – “I have a very understanding husband,” she says – and volunteers help her in the shop. This is bookshop as community service. “Books aren’t an industry where you’ve got a great profit margin,” she says. You work 15-hour days and you don’t get paid. It has to be a love.

Rogan chooses books with her community in mind. “I want every child to be able to walk in the shop and see themselves on the shelf – a child who is going through a family breakup, a child who has multiple sclerosis, a child who is autistic, a child who is going through some kind of gender identity issue – because it will make them feel included and it will make them feel like they’re important. I would always do that over selling a million copies of the latest commercial hit.”

She says that locals send her emails with a link to Amazon asking her to order a book. When she tells them they could buy it cheaper if they ordered it themselves, she says they tell her: “Amazon doesn’t play with my kids; Amazon doesn’t bring authors to Bedford; Amazon doesn’t recommend books when my child is going through hell and needs something to lift them up.”

Julie Danskin, 30, manager of Golden Hare Books in Edinburgh

Julie Danskin has been running Golden Hare Books for the past three years and says the store is “one of the most rewarding, challenging and downright joyful experiences of my life. Together with a small team of booksellers and a dedicated owner we have grown our bookshop from a struggling business to a thriving one.” When she took over the shop, she says, “it was always very beautiful, but it felt like you weren’t supposed to touch things and it didn’t do that many events. We decided we needed to be a pillar of the community.”

The shop moved from a more touristy area to Stockbridge in the north of the city, which is populated by “lots of young families”. Now, instead of relying on passing trade, it has been able to bed itself into a community. “We do a mixture of events in the bookshop,” says Danskin, “which have a very intimate, informal, sitting-room feel, and external events.”

The joy of bookselling, says Danskin, is making a connection with customers who may often be making a considerable emotional investment in the books they are buying. “You can really get to know people,” she says. “Some people come in and they are in incredibly vulnerable places in their life.”

Danskin worked at Waterstones for a year and rejects the argument that bookshops cannot pay a living wage. “If you’re owned by a hedge fund [as Waterstones is], paying a living wage is likely to be the last of your priorities,” she says. “We pay a living wage and are turning a profit. As far as I’m concerned, if we don’t have a good team that are being remunerated properly, then we are doing something terribly wrong.”

Ben Maddox, 25, bookseller at Waterstones in London

Ben Maddox has worked for Waterstones for 18 months at two different branches – one in central London and one in the suburbs – but also filling in elsewhere as required. He works a 37-and-a-half-hour week, is expected to work weekends and bank holidays with no extra pay, and gets paid £1,180 a month after tax. “It’s a bit grating,” he says, “knowing you can earn more in other retail industries where you don’t need any specialist knowledge, aren’t expected to pull as many overtime hours and where there won’t be huge events that require extra skills that won’t have been part of your training.”

Maddox complains about the “faux friendliness” of Waterstones. When he has been sent to cover in other stores at short notice, he says it was far from clear whether he could charge expenses for the extra travelling. He can – but he had to work that out for himself. “It is very vague,” he says. “It makes you feel as if you are the weird one for asking.”

He is keen to point out that it isn’t all bad. “Day to day, it can be tons of fun,” he says. “More than a lot of other retail roles could be, because you’ve got customers coming in who are interested in the things they are buying.” But he doubts whether he will stay at Waterstones and hopes to make it as a screenwriter. “Everyone has Waterstones has their ‘slash’,” he says, “the other thing they love. You get a lot of writers, actors and artists.”

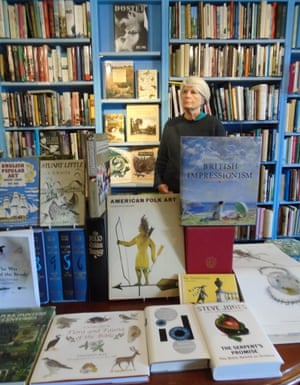

Joanna Chambers, 70, owner of Broadleaf Books in Abergavenny, Monmouthshire

Secondhand bookshops have had a tough time over the past couple of decades as online suppliers have taken off, but Joanna Chambers’s shop in the small south Wales town of Abergavenny is managing to stay afloat. What’s the secret? “I’m not on the main street and my rent is fairly low,” she explains. “I pick all the books myself and they are not books you’d see in the average shop. They may be secondhand, but they’re not falling apart. I try to make the whole shop look a bit different from anywhere else.”

She sells books online, too, but the shop is her real joy, and she says customers appreciate it. “The shop does better than online. People love the look and smell of it.” And the glorious serendipity, of course; the chance to find books you never knew you wanted. Chambers reckons she has more than 10,000 in stock, and buys most of them locally, often from the estates of people who have died.

Chambers came to bookselling in her 50s. She got the bug when she helped a friend who had a book stall in Abergavenny. She then ran a bookshop as part of an unsuccessful experiment to turn nearby Blaenavon into a books town. That ended in miserable failure. “I had to start again from scratch,” she says. But seven years ago, she set up Broadleaf Books, and this time the formula has worked. “I make enough money to keep the thing going,” she says. “You have to be a bit bonkers to sell secondhand books. You have to have a passion.” Chambers has no intention of giving up. “I’ll probably die in the chair,” she says with a laugh.

Khadija Osman, 24, manager of Round Table Books in Brixton, south London

Round Table Books in Brixton Market has been open for less than a week when I visit. You can smell the newness. The bookshop is the sister company of publisher Knights Of, which produces titles with a focus on diversity and seeks to “open windows into as many worlds as possible”.

Last year, Knights Of ran a pop-up bookshop in Brixton, and it proved so popular it hasturned it into a permanent store, supported by a crowdfunding campaign that raised £30,000 and a grant of £15,000 from Penguin Random House. The manager, Khadija Osman, graduated from university – she studied creative writing at Essex – last year. She has spent the previous six months working at Forbidden Planet – she is a fan of comic books and describes herself as a “big kid” who loves material aimed at children – and says she has always wanted to run a bookshop.

Osman, who grew up in a Somalian Muslim community in east London, says the shop will seek to champion writers from BAME backgrounds and stock a diverse range of books. It also plans to run storytelling events and writing workshops for local children. “We have to keep pushing the fact that it’s a fun thing, not a box-ticking exercise,” she says. “This is a children’s bookshop, first and foremost.”

Arlene Greene, 52, merchandiser for a branch of Tesco in Northern Ireland

Arlene Greene has worked for Tesco in Northern Ireland for 14 years. She originally worked for an outside company that supplied books, CDs and DVDs to supermarkets, but that company has been sold several times – “We are a commodity apparently,” she says – and now she is employed directly by Tesco. She sees herself as the store’s “book lady” and says she is one of an “army of minimum-wage workers, mostly middle-aged women” who check stock and look after the book displays.

Greene makes the point that Northern Ireland has very few independent bookshops; she says the emphasis has tended to be on secondhand books. That presents an opportunity to supermarkets, and she believes they are providing a worthwhile service. “Supermarkets are affordable to the masses,” she says. “They can be ruthless, but the fact that supermarkets sell books at least means the ordinary person on low pay can afford to buy a book when they want to. They’re just the top sellers, but at least we are still getting kids’ books out there at a reasonable price. That’s the important part of the story.”

What the book ladies aren’t allowed to do any longer is choose which books are sold. When the company was an independent supplier, they were given an input, but what to stock is now entirely a head-office decision, with the emphasis strictly on what will sell in large quantities. Greene finds this frustrating. “When Milkman by Anna Burns came out, it would have been nice to have showcased a prize-winner that came from Belfast,” she says. “We never received one copy. It wasn’t seen as a big enough seller for our market.” What she did get was endless copies of EL James. “They’re rubbish,” she says, “absolute rubbish, but I had to put it on every stand to get rid of it.”

Lesley Sheringham, 70, owns the independent bookshop Arthur Probsthain in central London

The Arthur Probsthain bookshop was established by Lesley Sheringham’s great-uncle in 1903. Based opposite the British Museum in central London and with a smaller outlet nearby at Soas University of London, it specialises in books on Asia, Africa and the Middle East. It is famous, much loved and in danger of going under – or perhaps morphing into something else – in the face of online competition.

Sheringham has worked in the shop, which is still family owned, for 50 years. “Most of the bookshops in this part of London have closed,” she says, “but we’re still hanging on. We had a very large stock of secondhand books built up over the years, but they are mostly sold on the internet now.” They have reduced the stock held in the shop and opened a tea room instead. “The tea room is really supporting the bookshop now,” she says.

What Arthur Probsthain, who was a distinguished orientalist, would have made of it is a moot point. “Bookshops have to try different things, but it’s been very tough,” says Sheringham. “It’s changed so much in the past 10 years. We don’t get the shop trade any more. Old customers come in and say: ‘What’s happened to all your books?’ But they haven’t been here for 10 years.” The museum is the building opposite is her point; this has to function as a shop.

Trudy Elliott, 26, bookseller at Waterstones in north-west England

Trudy Elliott has been at Waterstones for a year. It was her first job after graduating; she studied graphic design but realised she preferred books. “Everyone who works there loves books,” she says. “We’re all very passionate about the industry and about sharing books we love.” That’s the upside, but there is a sizeable (or, rather, not very sizeable) downside – the pay.

“It’s very low paid,” she says. “I’ve just been promoted to senior bookseller and I get £8.70 an hour. If I get promoted again [to lead bookseller], I’ll be on £9.39. That’s what you’re looking at as a bookseller. After that you have to go into management. There’s a mythical ‘expert bookseller’ level, but nobody seems to know what it is or what it’s pegged at.”

She rounds on the argument of Waterstones’ managing director Daunt that working for the company is inherently “stimulating”, as if that justifies the pay levels. “He was right when he called it stimulating,” she says, “but, unfortunately, a stimulating job doesn’t pay the rent.”

Elliott has other gripes, too. “It is exceptionally difficult to get a full-time position at Waterstones,” she says; her contract is for 30 hours a week. “There are also problems with rota scheduling, taking annual leave and communication from head office to the shops. Waterstones expects full flexibility from staff, even those on 12-hour contracts who need to work other jobs to afford rent and bills.

“Staff morale at Waterstones is very low.” she says. “There is a feeling that we are disposable to the company; it doesn’t appreciate or invest in its staff. We are still fighting our cause, though, and are looking at unionising and getting a stronger collective voice.”

Nia Owen, 57, owner of Caban in Cardiff

Nia Owen started her predominantly Welsh-language bookshop Caban in the trendy Portcanna area of Cardiff in 2002. She opened it primarily for her two sons, both of whom have autism. “My elder son [now 25] is quite able,” she says. “He’s very fond of books and because of his autism he’s very organised. His headmistress, in a passing comment, said to me: ‘He should work in a library or a bookshop.’” So Owen decided to provide him with that opportunity, giving up her job as a neuro-physiotherapist.

She says it cost her £10,000 to get started and that she got the shop off the ground in six weeks. “We didn’t have many books,” she says. “We didn’t have much of anything. But we had goodwill. We sort of played shop, and I think that has worked. People come in, they’re very loyal, they’re very regular and if they haven’t got any money I tell them to take something and pay next time they’re coming past.”

Owen, who grew up in a Welsh-speaking family in North Wales, sells Welsh-language books and English-language books with a Welsh connection. She has some paid helpers and other volunteers. “It’s a bit like a co-operative,” she says, “because everybody wants it to succeed. People come in sometimes just to talk. They tell us everything. I think we’ve replaced vicars and doctors.”

Gareth Thomas, 40, secondhand bookseller who has a stall beneath Waterloo Bridge in London

Gareth Thomas has been selling secondhand books as part of the Southbank Centre Book Market for 15 years. He started helping out on a stall when he was still at university, where he studied music technology, then took over one of the pitches – there are nine stallholders in all – when a licence became available.

He is quietly sitting next to his stall – long trestle tables covered in books and comics – when I arrive, while a couple of prospective buyers idly flick through his offerings. It is a blustery Tuesday and only the hardiest three of the nine stallholders have arrived to set up. Some of the others only appear at weekends – the busiest days – or on weekdays in the summer, when the riverside pavements are thronged.

Thomas pays the Southbank Centre £3,500 for his licence and targets a turnover of £40,000. His bestsellers are Penguin first editions – all neatly wrapped in plastic wrappers – and ancient hardback novels that he says appeal to tourists. He also has a sideline in US comics and yellowing copies of the Beano. “I try to get stuff you’re not likely to find in charity shops,” he says. “If you just have lots of copies of Dan Brown or chic-lit, people say: ‘I can buy that for a pound in a charity shop. Why should I pay £3 down here?’”

I ask if he always intended to devote his time to selling secondhand books while gazing at the Thames. “No,” he admits. “I had my sights set on being a famous music producer when I left university and this was just a stopgap.” But he says it suits him. While it can be “a bit hand to mouth, except in the summer”, he’s his own boss; he can turn up when he feels like – he recently became a father and has enjoyed having time to spend with his son - and his overheads are low. .

Robert Kane, 30, runs a ‘book bar’ at a fringe theatre in Belfast

Robert Kane is an actor and musician who works for Accidental Theatre in Belfast. As with most in fringe theatre, he has to multitask: not just performing but fixing lights, props, toilets, everything. But there is one extracurricular part of the job that, as a keen reader, he loves: helping to run the theatre’s book bar.

The book bar was born of a passion for booze rather than literature. In its original premises, Accidental didn’t have a licence to sell alcohol, so customers had to buy a book to get a complimentary drink. It does now have a licence for some of its shows, but the tradition continues. To get an alcoholic drink you have to become an instant book lover.

Kane admits the system initially baffles some theatregoers, but most quickly grasp it and even start to enjoy it. “It’s magical,” he says. “The book buying has taken on a life of its own. People end up spending more time looking for a book than talking to the people they’ve come to the theatre with.” He reckons about 80% of customers keep the books they have chosen; the other 20%, more interested in the booze than the bard, leave them to be recycled. “It’s very seldom that people are only interested in the drink and take the first thing that comes to hand,” he says. “Most look for something they really want.”

Some get so immersed in choosing a book that they don’t leave time to collect the drink. “Sometimes, the five-minute bell sounds and they’re still looking,” he says. They are allowed to pick a provisional book, get their drink and come back later to continue their search. Kane thinks the slightly bizarre convention is perfect for a fringe theatre. “It’s a lot of fun,” he says. “It’s playful and sets us apart from other venues, addressing the fact that we are fringe and slightly absurdist.”

The theatre’s patrons donate books and a couple of local bookshops also give it books they no longer want. “What is on our shelves is a game of roulette,” says Kane, “as our selection is entirely based on what is donated.” The bar has about 800 books, which are constantly refreshed, rather like the audience.

Pseudonyms have been used for the Waterstones booksellers and Tesco merchandiser.