A Radical Bookstore in Southern Appalachia: Firestorm Books & Cafe

Supporting Grassroots Movements Since 2008

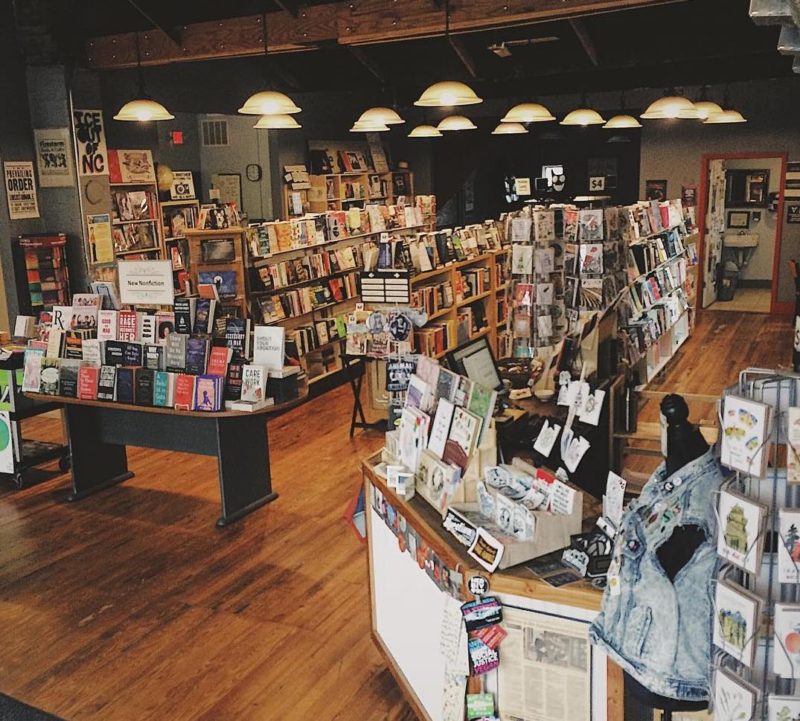

Firestorm Books & Cafe

is a collectively-owned radical bookstore and community event space in

Asheville, North Carolina. Since 2008, Firestorm has supported

grassroots movements in southern Appalachia while developing a workplace

on the basis of cooperation, empowerment and equity.

What’s your favorite section of the store?

Jazmin: I like our Family & Relationships section and I really enjoy our Worker Picks shelves. I think it says a lot about the people who work here and our personalities.

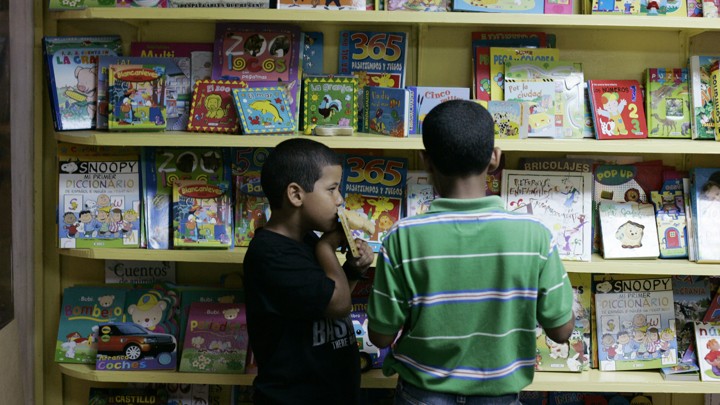

Libertie: My favorite is our kids’ section because it’s our newest and I’m really fond of the way we display our picture books and how immersive it is. When people walk into the space they have a really visible reaction to it. And also I’m just into adults reading middle grade.

Article continues after advertisement

Mic: It’s really hard to pick

one section but I think I’m going to go with Mind & Body. It’s an

exciting alternative to the popularity of Self Help, so I like going

over there and getting an eclectic mix of topics that in our culture are

often separated. You get Philosophy or Psychology over in one section

and Health in another section. I like that we make the connection

between the two.

Beck: For me it’s a toss-up between our kid’s section and our Sci-Fi & Fantasy section, where so much of that sweet, sweet dystopia lives. And that’s pretty much all I want to read right now as I watch the world shatter around us.

Libertie: Wow. No one chose Feminism or Anarchism! There goes our credentials as a radical bookstore.

What would you say is your bookstore’s specialty?

Beck: We bill ourselves as a

“social movement bookstore.” That means we lean in way harder than most

other bookstores on social movement history and contemporary texts about

anarchism, feminism, and socialism.

Libertie: And that’s really echoed in the other sections, too. For instance, rather than only finding queer titles in the LGBTQ section, you’re going to see strong representation in Biography and Fantasy.

I would also have to mention Herbalism.

I’ve been to a lot of other rad, collectively-run bookstores and they

never have an Herbalism section. It’s one of our strong sections and

it’s right next to other uncommon sections like Mycology, Fermentation,

and Wildcrafting. And that speaks so much to the character of our

community which has a deep interest in traditional health modalities and

connection to the earth.

Do you have bookstore pets or animal regulars?

Beck: Santiago! He’s perfect. He’s scared of everything. Santiago spends a lot of time shivering on the couch until his human puts a sufficient number of layers on top of him.

Libertie: Santiago is bilingual!

What’s your favorite book to hand-sell?

Jazmin: I’ve talked so many people into buying bell hooks, including her children’s books. You tell a customer that it’s “all about love” and *bam* FEMINISM! You gotta sneak it in there a little bit.

Libertie: We have so many good books to hand-sell, but for me, Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars by Kai Cheng Thom stands out. Both because it’s an incredible book and because I have, as of yet, basically never encountered anyone who has read it. It’s my go-to magical realist queer biography that’s obscure on account of being published by a small press in Canada.

Beck: I’m obsessed with Severance by Ling Ma, and I want to tell everyone about it. I feel like I should be able to say “anti-capitalist horror-satire” and have people fall over themselves to get their hands on this book, but I’m learning that everyone else’s favorite books don’t necessarily fill them with an overwhelming sense of physical and existential dread. If I see Margaret Atwood or Carmen Maria Machado in your hands though, you’re fair game.

Mic: I like to connect Parable of the Sower with Emergent Strategy. It’s a popular title and people either know Adrienne Maree Brown or they’ve heard of her podcast. For me the book connects so strongly to Octavia Butler’s work. When I see people looking at Parable of the Sower, in particular, I encourage them to read Emergent Strategy because it talks about applying some of what the main character is attempting to utilize in their own life.

If you had infinite space what would you add (other than a bar/restaurant)?

Libertie: We used to have a co-operative member who insisted that we open a bowling alley slash laundromat called “Pins & Spins.” Julie started advocating for this back in 2014 when we were looking for a new location and, although it didn’t pan out, they’ve kept their advocacy up very consistently ever since.

Beck: The bowling alley is lost on me, but I am enchanted by the laundromat—so convenient!

Mic: I love laundromats. There’s just so much space with the floor open and the machines along the wall. People could talk about books while folding their laundry. It would dovetail with the bookstore-as-community-space.

Libertie: Somebody did tell me recently that they had a dream in which Firestorm added a shooting range that also served pies. [laughs] Apparently we had a big sign that said “all people deserve affordable access to firearms and pie.” I don’t think that would go over very well with most of our customers.

What’s your favorite display?

Beck: Definitely my favorite display was the window we did in support of the national prison strike in August. We packed our front window with abolitionist literature and had “Prisons Are for Burning” with a lit match painted on it for like two months. Some folks were very fussy about it, and there was a massive thread on a local politics Facebook page debating the merits of our message.

Libertie: Definitely the most buzz Firestorm has ever received for a display!

Beck: Oh, and our enamel pin selection is displayed on a jean vest, which is very cute. That deserves a mention.

How do you use the bookstore to build community?

Mic: We have a big community room that is available to use free of charge for various events and meetings. Last year we hosted over 200 unique events plus regular meetups and discussion groups. Our ability to maintain the community room is supported through our Community Sustainers Program. In exchange for a monthly contribution, sustainers receive a range of benefits like discounts on purchases, a monthly mailer of our calendar of events, small giveaways, and frontlist titles handpicked by our collective. As we continue to grow the program, we hope to expand opportunities for sustainers to be involved with our space.

Libertie: Firestorm is a little unique in that it was created as a community event space first and a bookstore second. When we opened in 2008, we sustained ourselves as a cafe and then evolved into a book space, but the commitment to providing grassroots community resources never went away. In a sense, the business is just an engine to support social movement work. I don’t know of another bookstore that started that way, although there are others doing similar work. We now understand ourselves as part of the book industry, but that came second. We started as community organizers.

Mic: Another thing I love about our ability to build community is that it extends well beyond Asheville. As a ten-year-old worker-owned cooperative located in Southern Appalachia, we often hear from folks who choose to travel to Asheville specifically to visit Firestorm. Whether they heard from a friend or saw us at a book fair nearby, I love that we serve as a destination point and place of connection for queer youth or social movement organizers who might not have a space like this in their rural communities.

Libertie: I guess this is the time to mention that we’re currently in fight with the city! [Laughs.] It’s been covered elsewhere, but our commitment to community has gotten our store into some trouble. The zoning department claims that we shouldn’t be hosting non-literary events. We feel really fortunate to have the support of other local bookstores and our community, but our hearing is [in March] and we’ve had to divert a lot of resources to defending our co-op and the resources we host.

What’s your favorite thing to sell at the bookstore that’s not a book?

Mic: I like the “Please Kill My Enemies” iron-on patches, primarily because people seem to get so much joy out of them. They see them, they giggle, they show a friend, and then they buy one.

Libertie: Yeah I would actually say that everything from Silver Sprocket, where we get that patch, is my fave. I was thinking about another patch that says “I See Through All Your Bullshit,” which is from the same distributor. Their merch is extremely appealing aesthetically and also pokes at a unique cultural space.

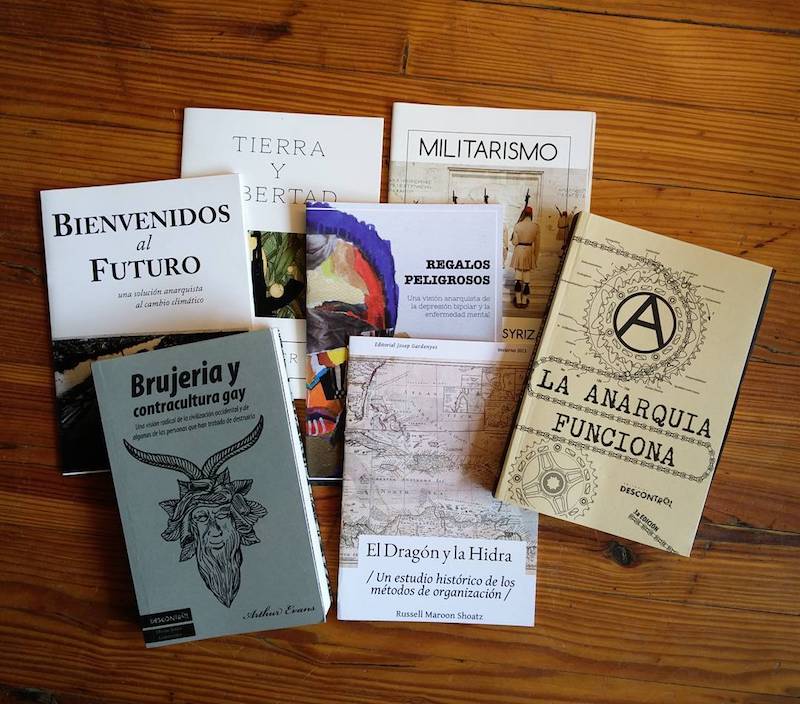

Beck: I wanna give a shout-out to our extensive zine collection.

Libertie: Right! Ten years ago when Firestorm opened, it was common for there to be zine collections in DIY spaces and radical bookstores. Over the last five years, those sections have really shrunk or disappeared from some of my favorite stores like Red Emma’s in Baltimore or Bluestockings in New York. That probably says something about the state of DIY publishing and how much takes place on the internet. And small books are increasingly affordable to produce on demand. So people who might have previously made really slick zines are now accessing more professional productions. But our patrons love zines and the price point is unbeatable at $2 to $5 each.

Beck: We pretty consistently receive little envelopes stuffed with zines from people all over the world who are like, “I made this thing! Let me know if people like them and I’ll send more.” And I love that at least once a week someone walks in with a folder of their zines to sell to us. So the bar to having something you created in a bookstore is low, and I like that.

What’s a children’s book that made you cry or that you think all adults should read?

Libertie: For me, Cory Silverberg’s Sex Is A Funny Word! The first time I read it, I thought, “Oh my god, where was this when I was a kid?” It consistently gets rave reviews from middle grade readers. If there are four children in the kid’s space, there’s never only one looking at Silverberg’s book. It’s either undiscovered or every child is studiously crowded around. I love that it deals with complex topics is a straightforward, non-jargony way while also being fun.

Mic: We have a collection of children’s books written and illustrated by Anastasia Higginbotham. With titles like Tell Me About Sex Grandma and Not My Idea: A Book About Whiteness, I really appreciate the way Anastasia encourages exploration of the “ordinary, terrible things” people might rather prefer not to discuss. The one that really got me was Death Is Stupid. Having lost a parent this past year, I saw much of my own experience in the emotional journey demonstrated through the eyes of a young child losing their grandma. Our culture can be severely lacking in well practiced and supportive collective grief. Still, when it comes to death, we are all in this together. In the meantime, how we live and how we remember is up to us, and there are lessons in this book (for children and adults alike!) for how we can cope, where we can ask for help, and how we can continue to grow along with a world that is always changing.

What’s a bestseller that could only be big in your town?

Beck: Witches, Midwives, and Nurses by Barbara Ehrenreich!

Libertie: Of which, notably, we have sold almost twice as many copies in 2018 as our second most popular title.

Beck: Which is What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia by Elizabeth Catte.

Libertie: Witches, Midwives, and Nurses was originally published as a pamphlet in the 1970s and was recently republished by The Feminist Press at CUNY in book form. It’s about the history of the patriarchal medical system and the eclipse of women’s power in society. A feminist classic that’s still culturally relevant and reads like it could have been written contemporarily. It covers territory similar to Silvia Federici’s Caliban and the Witch, but in a shorter, less academic format. Really it reads like a manifesto.