A is for Activist: why children’s books are getting political

Children’s literature is seeing a ‘seismic shift’ in diversity as authors say they want to make sure children of color see themselves represented

Several years ago, Susan Darraj’s 10-year-old daughter came to her with a question: “How come none of these books have Arab or Palestinian girls in them?” she asked.

The answer – that children’s chapter book characters are overwhelmingly white – didn’t sit well with Darraj, so she decided to change it. Or at least be part of changing it.

Now Darraj is at work on her debut children’s chapter book series, Farah Rocks. It tells the story of brave and intelligent Farah Hajjar, a girl who just so happens to be Palestinian American.

“People want to publish books about Arab girls who are dealing with hijab, things like that,” Darraj said. “I want to show my characters living normal everyday life.”

The questions of representation that have upended Hollywood, television and politics in recent years are now hitting the world of children’s literature hard. Already this year, several young adult (YA) books have been pulled over representation concerns, following high-profile dustups.

They’re just among the recent ones to draw scrutiny.

After two picture books (including one listed among the New York Times’s top 10 illustrated books of 2015) were criticized on “racial insensitivity” grounds for depictions of smiling and compliant slaves, one book was pulled from the shelves, and the author of the other apologized and said she would donate her writing fee to charity.

Yet for all the backlash against cancel culture and ambient fears of overcorrection, reformers’ progress is obvious.

Last year, there were more books than ever written about black characters and for the first time in recent years, more than half were written by black authors, according to researchers at the University of Wisconsin, who have been tracking racial representation in children’s books for decades.

And in March, Nicole Johnson of the We Need Diverse Books campaign hailed the “seismic shift” in US children’s book diversity, pointing to new figures showing the number of books featuring black characters more than doubled in the past decade, while those featuring Asian Americans characters more than tripled.

Publishers are on the hunt for diverse books, even as rightwing critics decry the supposed sullying of children’s literatures with politically correct dogma.

The number of minority characters and authors has been steadily climbing since 2014, with authors of color winning a growing number of awards, including the Newbery medal and the National Book award for young peoplein 2018.

Yet despite all the gains and champagne-popping, sizable diversity gaps still persist in the industry: black, Latinx and Native authors combined still wrote only 7% of new children’s books in 2017, according an analysis by multicultural publisher Lee & Low Books.

Such numbers are particularly problematic in the realm of children’s books, where artistic expression lives alongside educational imperative.

“Books are windows and mirrors,” said early childhood education advocate Sara Rizik-Baer, paraphrasing the critic and scholar Rudine Sims Bishop. “They’re mirrors allowing children to see themselves represented, as well as windows into other people’s lives.”

She works for Tandem, Partners in Early Learning, a Bay Area not-for-profit that helps supply classrooms with multicultural and multilingual children’s books. Since learning faces is a key part of early childhood development, representation is particularly critical there.

“We really want to expose kids to all kinds of people and we also want to make sure that they see themselves represented,” Rizik-Baer said.

The importance of that is something she saw firsthand as a bilingual school teacher in East Oakland when her second-grade student, a Mexican American girl, drew a puzzling picture of herself and Rizik-Baer standing under a rainbow.

“¿Por qué somos rubias?” she recalled asking the girl, who was dark-haired like her. (“Why are we blonde?”)

The girl’s response – “Because we’re smart” – broke her heart and helped change her career trajectory.

“Oh my God,” Rizik-Baer recalled thinking. “She needs to see more examples of little girls who look like her who are also seen as being smart.”

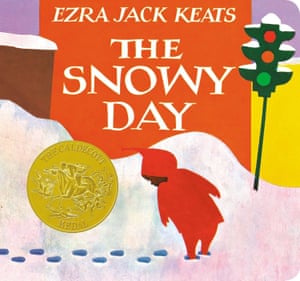

Such revelations about how children of color need faces they can identify with and be proud of – and not just when reading about Harriet Tubman – help explain why, for instance, classics such as The Snowy Day caused such a sensation.

When it was first published in 1962 it was revolutionary for a little black child to be depicted out in the snow playing like any other. Perhaps in drawing him the author, Ezra Jack Keats, who was born to Polish Jewish immigrants, was also giving shape to his family’s dreams of a world free from religious and racial persecution.

The book won a Caldecott medal and the character is still beloved (in 2017 the US postal service issued a series of Snowy Day stamps). But industry insiders question whether a book like that could be written today, given recent attention to the importance of letting underrepresented minorities tell their own stories, even as we continue to celebrate Keats’s legacy.

Meanwhile Elizabeth Acevedo, who swept young adult fiction awards in 2018 with her book, The Poet X, said recently at a lunch in Washington DC, that asan Afro-Dominican author she has no interest in upholding the supposed “nobility” of the classics. “I don’t write for that canon,” she said.

Such histories help illuminate the ongoing tensions in the movement, chief among them the literary world’s dual mandates to encourage creative expansion beyond the confines of one’s own lived experience, and to stop the appropriation of narratives belonging to the underprivileged.

The argument prioritizing the former was memorably made by the writer Lionel Shriver in 2016 when, in a keynote address at the Brisbane writers festival, she donned a sombrero to argue that “taken to their logical conclusion” representation arguments and all things politically correct “challenge our right to write fiction at all”.

The hat stunt predictably backfired. But larger questions underlying her argument are tougher to dismiss – specifically the question of what fiction writers are “allowed” to write about, given the real constraints and pitfalls of identity and privilege.

Still, some feel that positioning creativity against representation politics is a false tradeoff.

“No one’s advocating for ‘never do this’,” said Innosanto Nagara, author of the hit alphabet book A is for Activist. “I’m not an absolutist about it. I do believe in creative freedom.”

But he also thinks that if you are writing about people who have historically been harmed by dominant groups, your responsibilities to them as an author are great, and require a special level of care and consideration.

“Our choice around who we portray and who becomes the face of a story is how we can help people either be uplifted or erased. In children’s books in particular that’s true,” said Nagara, who is also a graphic designer and illustrates his own books.

Like Darraj and others, Nagara, was inspired to write his first children’s bookupon realizing the book he wanted for his kid didn’t exist. In his case it was an introduction to the activist community and what it means to be an activist, in words a child can understand.

What began as a self-published passion project quickly grew legs, and a few years later, Nagara has become a fixture in the children’s section of public libraries around the country, and a go-to interview subject as “an author of social change”. He has now published a handful of politically oriented books for kids and young adults – including My Night in the Planetarium, a resistance story from his childhood in Indonesia – the latest of which comes out this fall.

But in 2019 his political kids book will have plenty of company – and not just from the dozens celebrating black hair or the rise of women in Stem, or even more overtly political ones paying tribute to Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

There’s now a whole spread of children’s books responding directly to the political landscape and the phenomenon of Donald Trump.

Done poorly, such books can feel like opportunistic ploys for a buck – and some have been justly panned. Done well, they’re little works of art.

There are the subtle ones (I Walk with Vanessa), and the frank ones (A Child’s First Book of Trump). There are those that are domestically focused (We Rise, We Resist, We Raise Our Voices), and those published internationally (Dear Donald Trump). Just to name a few.

On Fox News, pundits have decried such advocacy as indoctrination.

“There has been in the last two years just an enormous outpouring of hysteria, vitriol – the same sort of thing that we’re seeing in the news, we’re seeing coming through children’s books,” Meghan Gurdon, the Wall Street Journal’s children’s book critic, told the Fox News host Laura Ingraham in December.

But one person’s indoctrination is another’s teaching core values. And where that might mean Jesus and the Bible on the right, on the left it more often looks like diversity and inclusion.