From The Atlantic:

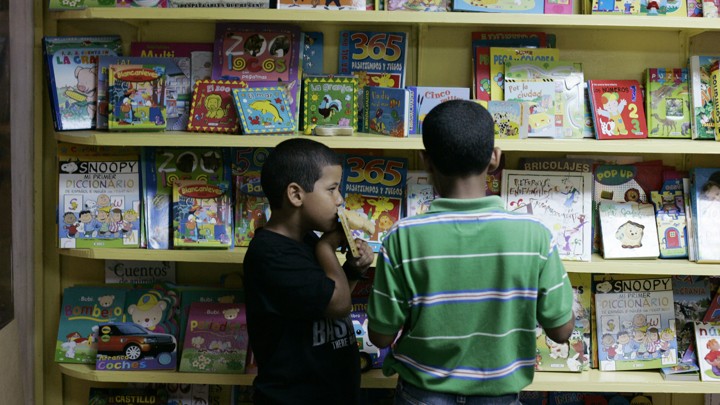

Boys Don’t Read Enough

Developed countries like the United States have seen a remarkable transformation in education over the last century: Girls and young women—once subjected to discrimination in, and even exclusion from, schools and colleges—have “conquered” those very institutions, as a report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) put it. Today, for example, women comprise a growing majority of students on college campuses in the U.S., up from around 40 percent in the 1970s.

One understated contributor to this development has been that girls routinely outstrip boys at reading. In two of the largest studies ever conducted into the reading habits of children in the United Kingdom, Keith Topping—a professor of educational and social research at Scotland’s University of Dundee—found that boys dedicate less time than girls to processing words, that they’re more prone to skipping passages or entire sections, and that they frequently choose books that are beneath their reading levels.

“Girls tend to do almost everything more thoroughly than boys,” Topping told me over email, while conversely boys are “more careless about some, if not most, school subjects.” And notably, as countless studies have shown, girls are also more likely to read for pleasure.

But it’s not just a phenomenon in the U.K.: These trends in girls’ dominance in reading can be found pretty much anywhere in the developed world. In 2009, a global study of the academic performance of 15-year-olds found that, in all but one of the 65 participating countries, more girls than boys said they read for pleasure. On average across the countries, only about half of boys said they read for enjoyment, compared to roughly three-quarters of girls. (The list generally excludes less-developed countries where girls and women tend to have lower rates of literacy than boys and men.)

But that girls read more than boys the world over doesn’t mean that biology is the driving force. As Lise Eliot, a neuroscientist at Chicago Medical School, said at the Aspen Ideas Festival in June: The brain “is a unisex organ,” meaning gender differences are mostly a result of socialization, not genetics. After all, boys tend to be more vulnerable than girls to peer pressure, and that could discourage them from activities like reading that are perceived to be “uncool.”

David Reilly, a psychologist and Ph.D. candidate at Australia’s Griffith University who co-authored a recent analysis on gender disparities in reading in the U.S., echoed these arguments, pointing to the stereotype that liking and excelling at reading is a feminine trait. He suggested that psychological factors—like girls’ tendency to develop self-awareness and relationship skills earlier in life than boys—could play a role in the disparity, too, while also explaining why boys often struggle to cultivate a love of reading. “Give boys the right literature, that appeals to their tastes and interests, and you can quickly see changes in reading attitudes,” he says, citing comic books as an example.

Topping suggests that schools ought to make a more concerted effort to equip their libraries with the kinds of books—like nonfiction and comic books—that boys say they’re drawn to. “The ability to read a variety of kinds of text for a variety of purposes is important for life after school,” he says.

Understanding why girls are so much more inclined to read might help eradicate what is proving to be a stubborn gender gap both in the U.S. and around the world: the lagging educational outcomes of boys and men. Reading for pleasure is, as the OECD has concluded, a habit that can prove integral to performing well in the classroom. “Any cognitive skill can be improved with practice,” Reilly says. “If girls are reading more outside of school”—if they’re doing so out of an intrinsic motivation rather than because they have to—“this provides them with thousands of hours of additional reading over the course of their development.”

And those extra hours pay dividends for years to come in the classroom.

ALIA WONG is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where she covers education and families.

No comments:

Post a Comment