Do The French Have A Name For It?

When it comes to teaching poor kids to read well, it seems they don’t.

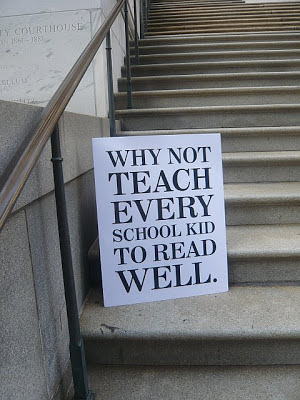

The French guy gets it. He looked at my sign this morning. I’d never seen him before. He stopped and said, ‘Exactly. That is an excellent sign. We have the same problem in France where I’m from. They don’t seem to recognize that unless the poor children are taught to read, they can’t do the other school subjects. Why don’t they know that?’ We talked for a few minutes. Both agreeing with each other that the kids need to know how to read well, before they can even know how to write. Reading is the foundation for all of it, we nodded together. We each took off one glove in the cold and shook hands.

I take an hour walk in the afternoons along the East River.

Yesterday I had an NPR show in my ears. I couldn’t listen to sports talk

yesterday with all the predictable groaning over the Jets and the Knicks. The

NPR show had on the author of a book about Benjamin Franklin’s sister, Jane. Jane

wrote many letters to her brother. The host asked if young women in those days

were taught to read and write like the young men were. The author replied that

they were definitely taught to read, so that they could read the Bible.

We had a Bible in our house when I was a kid. It had a soft

light green leather cover and the edges of the pages were shiny gold. It had my

parents’ wedding date in the front and the birth dates of the three kids. I

stared at my mother’s perfect handwriting in it many times. It was on an end

table in the living room and sometimes I would pick it up by the spine and

dangle it with the pages facing the floor. It was very thick and heavy and I

liked the way it felt holding it that way. Not one word of it was ever read in

our house. Not by me or my sisters or my parents or my grandmother who lived

with us before she died or my aunt who lived with us for awhile. We were

Catholics, and Catholics were not encouraged to read the Bible. Protestants

read the Bible. Not Catholics. We weren’t supposed to learn on our own. We were

supposed to hear the priest read passages from it during Mass on Sundays, and

then tell us what it meant. I wonder if Jane had been Catholic if she would

have been taught to read so definitely.

On the #6 train a week ago my eyes landed on the stunning cheekbones

of an Asian mother reading a book to her pre-school daughter. It was a paperback

chapter book and the mother read it so purposefully that the child, even as she

slid around on the slippery subway seat, kept her eyes glued to the important book

and her mother’s voice. The mother didn’t put the book in her big canvas tote

bag until the train stopped at the last station. A young black kid,

junior-high-age maybe, in a Yankee cap and basketball shoes, with nothing in

his hands, across the aisle from them, watched the angel mother read as

appreciatively as I did.

Sometimes when people walk by the sign and me, they’ll smile

a full, warm smile and say, ‘Ain’t that the truth!’, and I’ll say back, with

total assurance, ‘It could change the world.’ I don’t always think to say that.

But that’s what I wish I’d have said to everyone who’s made a comment. It’s

what I believe. It’s why I hold the sign. This will be my third winter standing

with the sign for an hour every weekday on Chambers Street. Some of the

passers-by who haven’t seen me till this year are surprised I’m there in the

cold weather. I like being there in the cold. This morning I had a dull headache

from the Guinness and the Jameson I had last night at a tavern across the

street from my Third Avenue apartment. I went there to watch all the games on

the big screens, after I’d read another chapter in Donna Tartt’s spectacular

new novel, The Goldfinch. An earlier me might have skipped class on

such a morning after or taken the day off from work. But a little headache is

nothing now to a guy who thinks his sign’s message could change the world.

Here are two paragraphs from Tartt’s book. In them,

13-year-old Theo has come from the Upper East Side down into the Village,

looking for someone who might have an important answer:

And so it was that around half past eleven, I found

myself riding down to the Village on the Fifth Avenue bus with the street

address of Hobart and Blackwell in my pocket, written on a page from one of

those monogrammed notepads Mrs. Barbour kept by the telephone.

Once I got off the bus at Washington Square, I wandered for

about forty-five minutes looking for the address. The Village, with its erratic

layout (triangular blocks, dead-end streets angling this way and that) was an

easy place to get lost, and I had to stop and ask directions three times: in a

news shop full of bongs and gay porn magazines, in a crowded bakery blasting

opera, and of a girl in white undershirt and overalls who was outside washing

the windows of a bookstore with a squeegee and bucket.

Last Sunday morning two young women and a guy-friend of

theirs came to my apartment with a movie

camera. Some months ago one of them

had come across one of these newsletters in a bookstore downtown and got a hold

of me. She liked the message in the newsletter and wondered if she and her old

college friend, who like her had been a film major, could shoot some kind of

film about me and why I was so interested in every kid learning to read well.

Of course, I said, whenever you want.

So, they set up their lights and put the camera on a tripod

in front of me, sitting there on my couch in one of my everyday long-sleeve

blue t-shirts, with a bad haircut. The one girl asked questions while the other

two monitored the focus and the sound. I talked for the better part of two

hours. It was like Freudian analysis. I was allowed to talk without interruption.

I learned things, as I said whatever came to mind. I said I loved the poor city

kids and was outraged that they weren’t being taught to read. I said it was a

sin that they were being denied the chance to be full members of our culture. I

said the sign says I love them, and the French guy loves them too. So do other

people who smile at the sign in a certain way. Sometimes my eyes almost water

when I see a warm face connect with the sign.

When the young filmmakers packed up their stuff and said

thank you, we’ll be in touch, we shook hands goodbye. And after I’d closed the

door behind them, I broke down in tears for a few seconds.

.jpg)

.jpg)